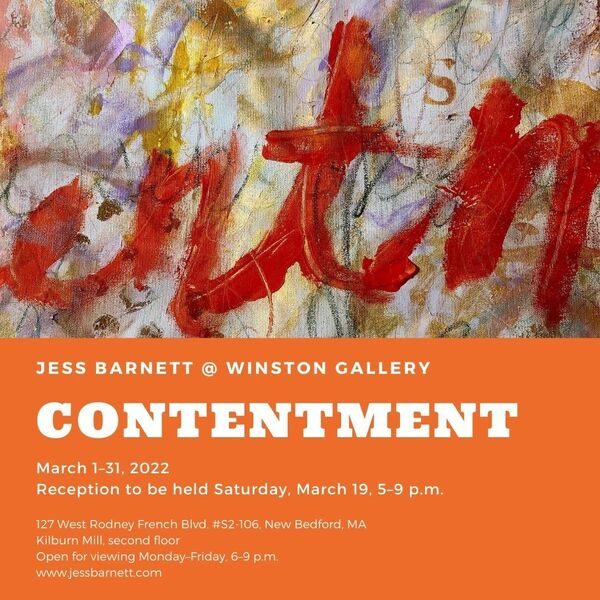

Contentment (2022)

Contentment at Winston Gallery, March 2022

gave me a box full of darkness.

It took me years to understand that

this, too, was a gift.

The Contentment series was born on New Year’s Eve of 2021, the last evening of the second calendar year of the pandemic. The grief inspiring the series was born four years earlier, however, on May 2, 2017, when I was told of my mother’s sudden passing after her yearslong battle with depression.

Like a car crash or home invasion, grief is a massively traumatic event, affecting everything—sleep; emotional state; love, friendship, and work relationships; ability to communicate; ability to work; and general resilience, among others. For me, after being hit broadsided with my mother’s death, grief was sudden but sticking, spreading like a cancer into every area of my life. I became suicidal, faced a renewed struggle with my own battle against alcoholism and addiction (or substance use disorder [SUD], as it’s become more acceptable to call it), lost jobs, entered and struggled within harmful romantic relationships with people who had their own SUD and mental health challenges, and, finally, checked myself in to the hospital and then a residential facility in New Hampshire.

Contentment is titled as such in a somewhat tongue-in-check manner, as I’ve sought that state of mind since my adolescent years. Due to perseverance, 12-step program participation, and therapy, I am finally more content than I ever was previously. The series title is also slightly ironic given the scribbled chaos contained in some of the series’ paintings, but that’s intentional; dealing with grief feels like constantly pushing against waves in a turbulent sea. I have to let myself feel the emotions and be tossed about by those waves in order to reach any semblance of contentment and serenity.

Besides the themes of grief and a struggle toward serenity, the Contentment series holds within it another theme: the carrying of materials from one piece to the next. Each piece borrows from another at least one element. Materials include the more typical (acrylic paint, pastels, colored pencils) and the less usual (Scrabble tiles, eyeshadow, pokeberry ink). This secondary theme also shows up in the seemingly random sprinkling of English letters throughout the series. While some of the letters, when combined and rearranged, spell out the word contentment, others are in actuality “random” and their incorporation meaningless in the sense that they don’t spell out any series-related words. Their inclusion echoes the loss of my ability to communicate due to my grief, a phenomenon that has fortunately lessened recently due to therapy and an improvement in my self-esteem.

Lastly, the series embodies the mixture of deep melancholy and giddiness that has characterized my mental state since childhood. I hold within myself alternating emotions of profound hope and dark cynicism, although I most often strive for the former to win over the latter. The majority of pieces (including the three eponymous paintings, Contentment I–III) use a pastel palette reminiscent of a less saturated version of Lisa Frank,1 although a few, including Fabrication and Bottom Line, incorporate a more somber palette. The letter by Rupert Brooke to F.H. Keeling in September 19102 is an exquisite presentation of this emotional fusion, particularly the lines that follow:

What happens is that I suddenly feel the extraordinary value and importance of everybody I meet, and almost everything I see. In things I am moved in this way especially by some things; but in people by almost all people…. I roam about places and sit in trains and see the essential glory and beauty of all the people I meet…. Half an hour’s roaming about a street or village or railway station shows so much beauty that it’s impossible to be anything but wild with suppressed exhilaration.

I believe that these feelings—just like the gift that Mary Oliver calls grief—are an unmerited gift; without them, I couldn’t have survived my mother’s loss.

1 Designer, artist, and businesswoman who influenced me beginning in my elementary school years; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisa_Frank and https://shop.lisafrank.com/.

2 “Do not leap or turn pale at the word Mysticism (spiritual awakening), I do not mean any religious thing, or any form of belief. It consists in just looking at people and things as themselves—neither as useful nor moral nor ugly nor anything else; but just as being. At least, that’s a philosophical description of it. What happens is that I suddenly feel the extraordinary value and importance of everybody I meet, and almost everything I see. In things I am moved in this way especially by some things; but in people by almost all people. That is, when the mood is on me. I roam about places and sit in trains and see the essential glory and beauty of all the people I meet. I can watch a dirty middle-aged tradesman in a railway carriage for hours, and love every dirty greasy sulky wrinkle in his weak chin and every button on his spotted unclean waistcoat. I know their states of mind are bad. But I’m so much occupied with their being there at all that I don’t have time to think of that. I tell you that a Birmingham gouty Tariff Reform fifth-rate business man is splendid and immortal and desirable. It's the same about the things of ordinary life. Half an hour’s roaming about a street or village or railway station shows so much beauty that it’s impossible to be anything but wild with suppressed exhilaration. And it’s not only beauty and beautiful things, but in a flicker of sunlight on a blank wall, or a reach of muddy pavement, or smoke from an engine at night, there’s a sudden significance and importance and inspiration that makes the breath stop with a gulp of certainty and happiness. It’s not that the wall or the smoke seem important for anything, or suddenly reveal any general statement, or are rationally seen to be good or beautiful in themselves, —only that for you they’re perfect and unique. It’s like being in love with a person, one is extraordinarily excited that the person, exactly as he is, uniquely and splendidly just exists. It’s a feeling, not a belief. Only it’s a feeling that has amazing results. I suppose my occupation is being in love with the universe” (excerpt from letter dated September 20–23, 1910).